Just another body waiting for another procedure.

It was only a week since the surgeon had inserted the tiny metal clip into my breast -my first real marker that this was happening, that cancer had taken up residence in my body and was now being mapped like hostile territory. And now here I was, facing the next procedure, a bigger one, the one that would set the stage for chemotherapy: the insertion of a portacath.

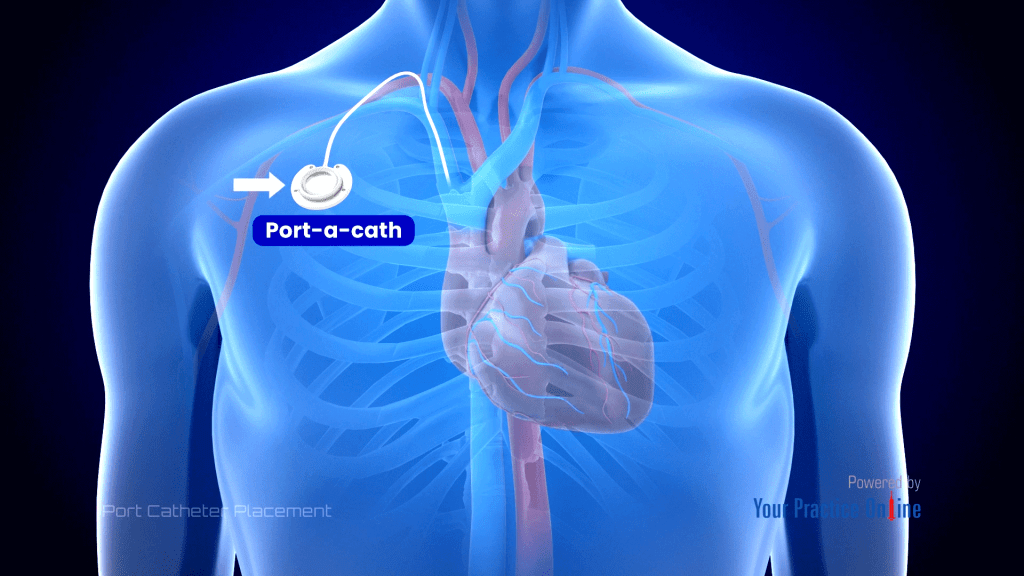

The word itself sounded mechanical, like a docking station for a spacecraft. In truth, it was not that far from the mark. A portacath – sometimes simply called a port – is a small medical device placed under the skin, usually in the chest. It consists of two parts: a small round chamber, about the size of a five-cent coin but deeper, and a thin flexible tube, or catheter. The chamber is implanted beneath the skin, while the catheter is carefully threaded into a major vein, travelling upwards toward the jugular and then down into the superior vena cava – the large vein leading directly to the heart. Once in place, the port becomes a kind of private entry point, a hidden gateway through which chemotherapy drugs can be delivered directly into the bloodstream.

The alternative would be a cannula, those plastic tubes that nurses slip into the veins of your arm or hand. For everyday medications, blood tests, or fluids, cannulas are fine. But chemotherapy is not an everyday medication. These drugs are corrosive, harsh, toxic enough to burn healthy tissue if they leak outside the vein. They can destroy smaller veins after repeated use, leaving arms bruised, scarred, and unusable. A portacath, by contrast, bypasses all of that. It protects the veins, spares the skin, and makes treatment easier. Nurses can simply insert a special needle through the skin into the port’s chamber, access the vein directly, and start the infusion. I was told that once it was in, I would barely notice it. It would sit beneath the surface of my chest, a small, raised bump under the skin, invisible under clothing, invisible to everyone but me.

It sounded neat, clinical, efficient – almost like a design solution to an engineering problem. But when I learned how it was actually implanted, the neatness of the explanation fell away, replaced by raw horror. The surgeon would cut a pocket beneath the skin on my chest, slide the chamber in, and then thread the catheter through my vein until it reached my heart. I would not be under general anaesthetic, as I had assumed. No, they assured me: this was a “minor procedure,” performed under twilight sedation. I would be awake. Awake!

The word replayed in my mind for days before the surgery. Awake while they cut into my chest. Awake while they pushed plastic tubes into my veins. Awake while they stitched me back together. The thought was almost unbearable, and yet there was no alternative. If I wanted chemotherapy, if I wanted my best chance at survival, the portacath was the price of entry.

I arrived at the hospital at seven o’clock in the morning, convinced in my naïveté that I would be first in line, “first cab off the rank,” as the saying goes. Instead, I walked into a crowded waiting room filled with the pale, the frail, the visibly suffering, each person clutching their own story, their own diagnosis. Some were hunched over in wheelchairs, others sat listless with hospital bracelets already dangling from their wrists.

There was no fast track for cancer patients, no VIP queue for chemotherapy initiates. I was just another body waiting for another procedure.

Hours crawled by. I sat there in a thin hospital gown, my clothes folded in a plastic bag at my feet, daytime television droning on in the background. I stared at the screen but absorbed nothing, my mind flipping restlessly between dread and numbness. By noon I was stiff, restless, and beginning to wonder if they had forgotten me. When finally my name was called, nearly five hours later, I stood up shakily and followed the nurse down the corridor.

The pre-op area was brisk and businesslike. A nurse asked me to state my name, date of birth, and the reason for my visit. The words felt alien in my mouth: “I’m here to have a portacath inserted so I can start chemotherapy.” Saying it out loud made it sound like someone else’s life, not mine. She smiled kindly, assured me I would be comfortable, that I wouldn’t remember a thing. Twilight sedation, she promised, was like drifting off into a half-dream, a place outside of time. I wanted to believe her. But the reality that followed was nothing like the soft blur of dreams.

The operating theatre was not the place of television dramas where patients are wheeled in unconscious, already surrendered. I had to walk myself in, past bright lights and stainless-steel trays, past masked figures busying themselves with instruments. I climbed awkwardly onto the operating table, lay down, and turned my head to the side as instructed. A drape was placed over me, leaving a small gap near my face so the nurses could check on me. From that tiny opening I could peek out, but mostly I saw fragments: gloves, gowns, quick movements. I heard the doctor enter, briskly briefed on who I was and what was about to be done.

To them, this was routine. To me, it was the most terrifying moment of my life.

Then the cutting began. I felt it instantly. A sharp slice, a hot sting, pressure deep in my chest. My feet jerked uncontrollably, writhing against the sheet. I gasped, called out, told them I could feel everything. There was a sudden flurry of voices. Someone muttered that the twilight sedation hadn’t been administered. Nor had the fentanyl, the pain relief that should have dulled everything. Machines beeped, hands scrambled. But it was too late – the procedure was already underway.

I lay there, every nerve on fire, aware of every push and tug as the surgeon created a pocket under my skin, slid the port into place, and began threading the catheter through my vein. I tried to hold still, tried not to scream. My body betrayed me: my feet kicked, my chest heaved, tears ran down my temples into my ears. Time lost all meaning. It could have been minutes or hours; all I knew was the searing immediacy of pain.

At last, as the procedure was nearly over, the machines flickered to life. A flood of anaesthetic rushed through me, a delayed reprieve. I was given a double dose of fentanyl just as the final stitches were being sewn. The room spun violently, nausea gripped me, and I thought I would vomit right there on the table. But it was done. The port was inside me now, my unwelcome new companion.

They told me to sit up. My body resisted, weak and trembling, but somehow, I managed. I was guided into a wheelchair and rolled into a recovery ward, a long row of patients fresh from their own surgeries. We sat there together, a silent line of groggy, pale figures, our eyes glazed, our bodies slumped.

Through the fog, I heard familiar voices – my husband’s, my son’s – calling for me. I looked up, and when they saw me, I watched their faces fall. The shock in their eyes mirrored the horror I felt inside. I must have looked terrible: dazed, sick, pale, stitches tight in my chest, a new lump under my skin. I was no longer just their wife, their mother. I was a cancer patient, marked, altered.

Somehow, with help, I managed to dress, pulling my clothes over the tender new wound. By the time we left the hospital it was nearly 7 p.m. – a full twelve hours since I had arrived that morning. Outside, the world was dusky and indifferent. I was exhausted, nauseous, in pain, and terrified of what came next.

Because the next day was the real beginning. The port was in place now, ready for its purpose. Tomorrow, chemotherapy would start. Tomorrow the poison would flow through that little chamber under my skin, straight into my heart, spreading through my veins to hunt down every fast-dividing cell it could find.

That night, I could not eat, could not drink, could not think. All I could do was lie still, feeling the ache in my chest and the weight of what had just happened. The port had been sold to me as invisible, painless, forgettable. But in that moment, it was none of those things. It was a wound, a reminder, a symbol of what I was about to endure.

Leave a comment