I had swung through, but the room on the other side was unfinished.

The nurses told me first. Before the diagrams about drug cycles, before the list of possible side effects with their careful, professional voices – they told me my hair would fall out. It arrived in the same clipped, clinical way other facts about cancer arrived: a line item to be acknowledged and filed away. “It will probably start about two weeks after your first chemo,” they said, as if that small, private catastrophe could be scheduled and contained like a clinic appointment.

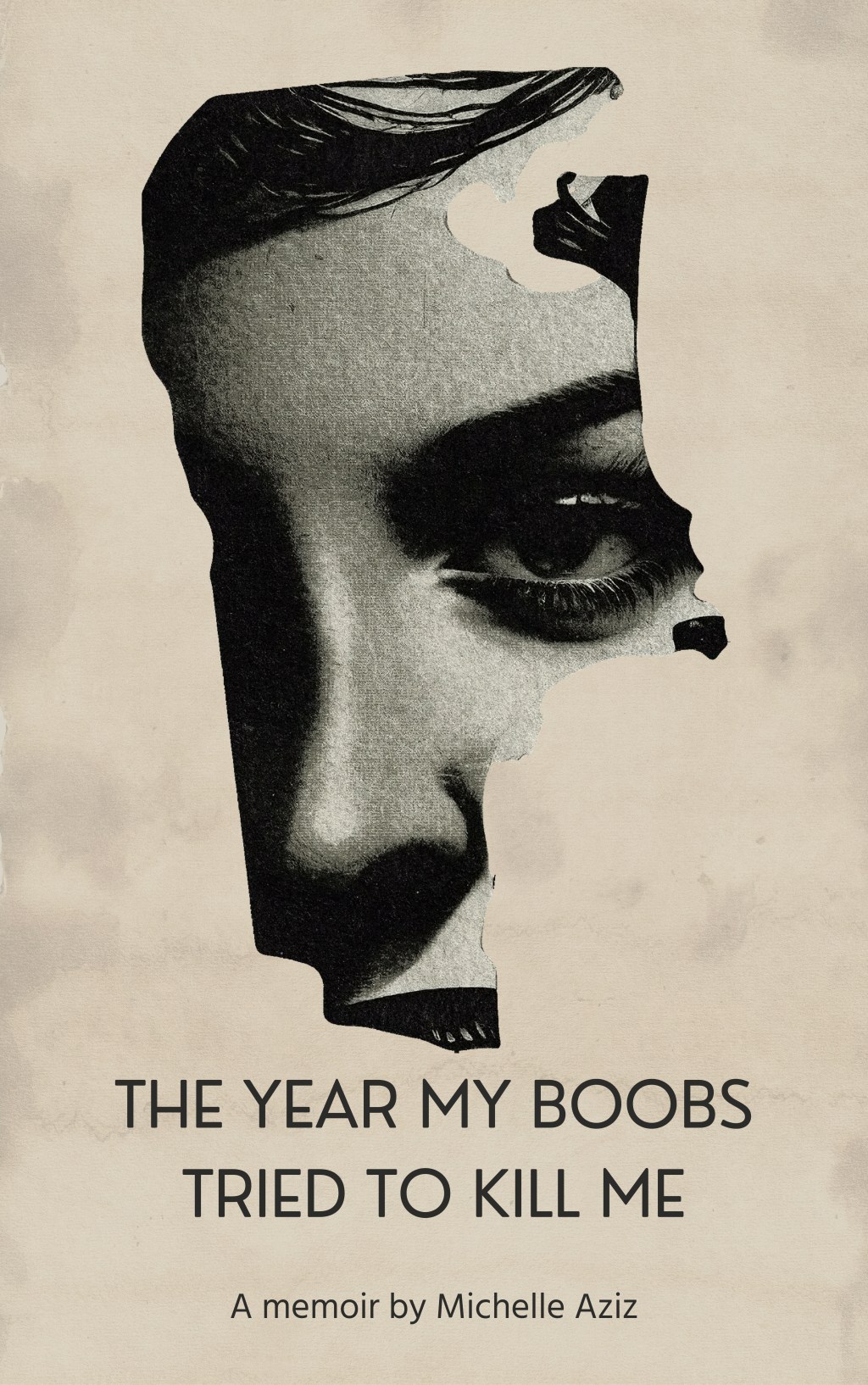

I had never really pictured myself without it. Pictures in pamphlets and cancer charity sites showed bald cancer women with soft lighting, pretty headscarves folded artfully, a glow like a deliberate filter. It is a tidy, dignified aesthetic: the woman who has lost something and is still somehow styled to reassure the viewer. Those images made it look almost ceremonial, almost pretty.

The reality of being told I would lose my hair was messy and immediate, and hit like a gut punch.

I oscillated between two options: wait for it to fall out in small, humiliating clumps, watching the shower drain collect my identity strand by strand; or choose the moment myself, claim it back in a single movement. There is a perverse cruelty in the second option – to shave my head meant to do something to myself that the disease might do to me anyway – but there was also a logic to it. It felt like an act of agency. If chemo was going to change my body, I wanted to choose how that change started. If my body would be altered, I wanted to be the one to pick the time and place. “One final act of control,” I told myself, which, at the time, sounded like a plan and a prayer.

Some women made it into an event – champagne, a hairdresser, friends, a ritual of bravery. There are photographs of it: laughter, confetti, solidarities woven into the moment. I admired those images. For a week I tried to imagine myself laughing in a salon chair with someone upending bubbly over my shoulders. I tried to picture friends around me, beaming support like a halo. I could not get there. Brave as it seemed, the idea of an audience felt performative and too exposing. I wanted the act to belong solely to me. I wanted silence and a door to close. So, I bought clippers and told myself I would do it in the spare bathroom, alone.

For a long time, I just sat and watched my hands. I told myself I would be calm, methodical; I would take each lock and make a ceremony of it. I think I thought I would feel something when I started. A rush of liberation. A deep, cinematic release. Instead, there was an odd disconnect, as if I were observing the scene from outside my own body. I grabbed handfuls of hair and hacked indiscriminately with scissors, not caring about neatness or the mess gathering at my feet. There was no ceremony. No tears. No dramatic sobs.

My husband watched from the doorway, his face a map of disbelief and something that looked a lot like pain. There was no scene of support, no shared laughter. Just us, confronting a new punctuation in our lives. Eventually I had to ask him for help. I couldn’t do the finishing myself; I couldn’t bear to decide how short was too short. He took the clippers with a careful tenderness, as if handling something fragile. He couldn’t bring himself to cut it all the way down, so what remained was a compromised truce: a lopsided pixie, uneven but honest. It was not the sleek, deliberate style of those glossy headscarf photographs. It was ragged and domestic, and in its very imperfection it felt true.

I sat on the edge of the bath afterwards and felt nothing at first. Nothing dramatic, no tidal wave of grief or liberation. I looked down at the pile of hair and simply started to sweep. The broom made a soft rasping noise against the tiles. I swept the evidence into a neat heap and carried it to the bin like someone taking out the rubbish. The anticlimax of it surprised me more than the haircut itself. No cheering. No songs. A quiet, solemn acknowledgement that this was happening.

I remember thinking about the images we see of women with cancer – the curated, comforting ones – and how they’re meant to make us feel better about the awful. But the reality is messier. There is stubbornness in the act of shaving your hair, even when done without fanfare. It is not always brave in the way others recognise. Sometimes it is simply practical. Sometimes it is private. For me it felt like stealing back a piece of agency: deciding when the loss would happen, choosing the small detail of timing, refusing to let the disease stage that particular scene for me.

That stillness – the absence of celebration – was not a failure of feeling. It was a kind of survival. In the days that followed, I realised the numbness had done its work: I had moved past the initial shock into the thing that came next. The shaved head made the illness visible to me in a way that tests and scans had not.

People react to a shaved head in ways you don’t expect. Some people avert their eyes, unsure how to look at a woman who doesn’t fit their quiet template for illness. Others reach for platitudes: “You’re so brave.” Often, they mean it as comfort, but it can sound like a mislabel. You don’t choose bravery the way you choose clothes; sometimes it is simply the thing you do to keep breathing. Hair loss changed the way people saw me and, more importantly, how I saw myself. It strips back the performance and forces you into a more direct encounter with who you might be without those layers. I was not yet ready to answer the question of who that person would be. The shaved head was a hinge; I had swung through, but the room on the other side was unfinished.

Leave a comment