April 2024 – Cycle two

By April 2024, I was on my second cycle of chemotherapy, and already the world had shrunk down to two places: my living room, and the hospital. Everything else – the shops, the parks, the simple pleasure of walking around my neighbourhood – seemed like a distant memory. I could barely stand, let alone walk for long periods of time. Walking through a shop was now impossible. Walking through a park was impossible. Even walking around my own house felt like a small expedition. I couldn’t drive. I could barely stand long enough to make my son’s lunch in the morning without feeling dizzy, like my body might just fold in on itself and drop to the floor.

My husband and son gently tried to coax me outside, taking me to the park and holding me up on either side as I shuffled along the boardwalk by the lake, tears slipping silently down my cheeks. I felt embarrassed by what I’d become, and guilty for putting them through it. Before long, I stopped trying to walk the loop and instead sat at a picnic table, watching them kick a soccer ball back and forth, wondering if I would ever have the strength to run and play with them again.

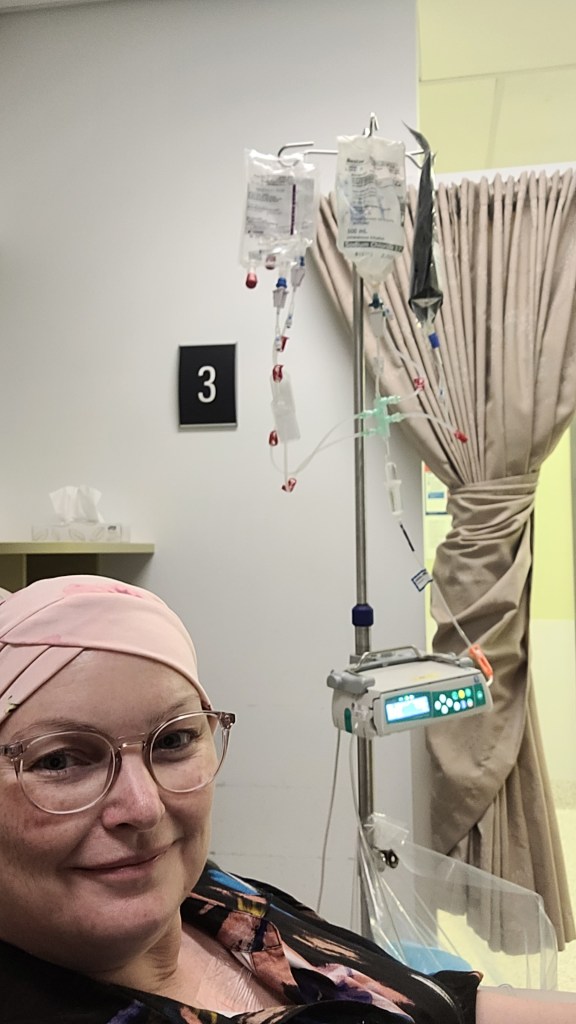

Chemotherapy, for me, came in three-week blocks. The first week was the “big one”, five straight hours tethered to an IV pole while a series of chemicals seeped into my body, one bag after another after another. The nurses always tried to be cheerful, efficient, warm. I would nod and smile and pretend I felt comforted by their brightness, but the truth was, I was scared out of my mind.

Weeks two and three were shorter, three-hour infusions of a different mix of chemo and immunotherapy, but they were no less potent. If the first week felt like being hit by a truck, the following weeks were like being hit by the same truck but from slightly different angles.

Days three and four after each infusion were always the worst. On those days, the steroids and anti-nausea meds wore off, and the full force of the chemicals took over. I could feel them inside me – thick, metallic, heavy – making my stomach sick and my bowels grind to a halt. I would then spend the rest of the week taking laxatives to try and get my insides working again.

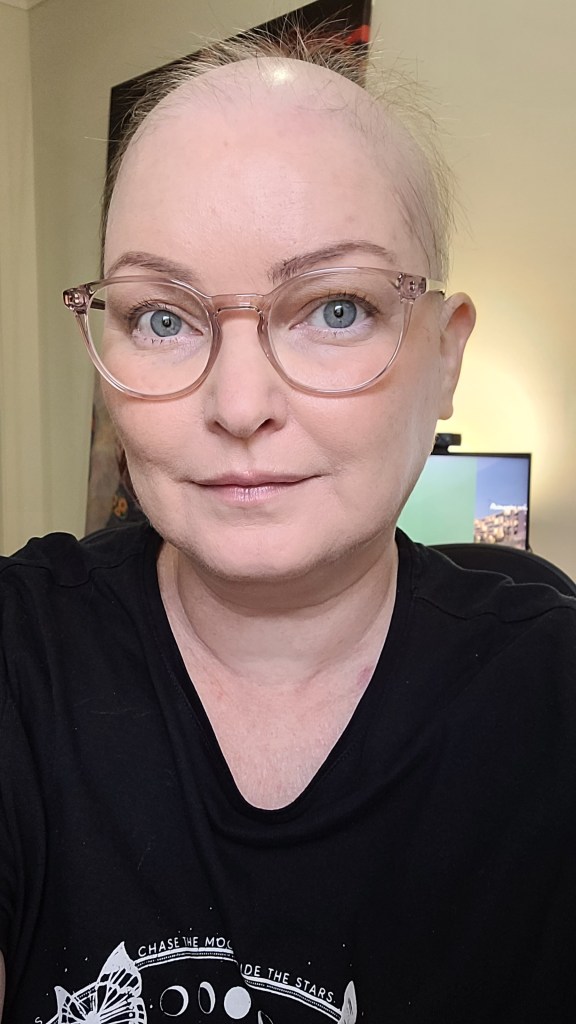

And through all this, I kept working. Full-time. Laptop on the couch, meetings through Teams, documents glowing on the screen, while my body deteriorated quietly beneath a blanket. I didn’t have the energy to sit at a desk anymore. My brain was foggy, my mouth tasted like metal, and some days my fingers felt too weak to type. But I kept going – out of habit, and out of fear of letting people down. I kept running training sessions for hundreds of people online, psyching myself up beforehand because I knew I’d have to address my gaunt, unsettling appearance the moment my camera switched on. Before each meeting, I felt a familiar surge of panic, worrying about how I looked, and whether my colleagues would start doubting my capability because of it.

Three times a week, I went to the hospital. Work, hospital, home. Work, hospital, home. That was my entire universe.

I stopped going inside the shops because my immune system was too suppressed. My blood counts were always borderline. A simple cold would have been catastrophic. So, on weekends, my husband and son would drive to Coles or Woolies, and I would stay in the car, seat reclined, blanket over my knees. They would run inside while I sat in the carpark watching people go about their day. Sometimes people would catch a glimpse of me in the car – pale as a ghost and almost bald – and do a double take. I have to admit; it made me laugh every single time.

Most days I lay on the couch in the living room with all the windows and doors open so the wind could blow over me, forgetting to eat and drink until I realised the sun was setting and my son would be coming home from school soon. People imagine cancer treatment as dramatic and cinematic, but honestly it is mostly monotony – endless hours waiting for your body to process the punishment you’ve willingly submitted to. But I didn’t really mind the stillness. There was a strange peace in surrendering completely to survival mode. The fight, in many ways, had already been decided by the chemicals coursing through me. My job was simply to endure them.

Cycle three began with what I referred to as the “big chemo” – the five-hour monster infusion that always marked the start of each round. By this point, my port still looked red and raw, as if it had been sewn into my chest the day before rather than a month earlier. The stitches refused to dissolve. Some had started poking through my skin like tiny black wires pressing out from underneath. Every time I looked at it, my stomach flipped.

The nurse assigned to me that day tried his best to access the port, but it wasn’t cooperating. He pressed, he angled, he paused to apologise softly. The port remained stubborn, sitting just under the skin, tender and angry, refusing to let the needle in. I was in the chemo pod – a large open room with eight reclining chairs facing each other, occupied by someone wired to their own drips. We were like a strange little community of strangers, thrown together by this shitty disease, various cancers all slowly eating away at our insides. There was nowhere to look but at each other, and I could sense everyone glancing at me curiously, wondering why it was taking so long to get hooked up to the IV.

After a while I became obvious that the stitches above my port would have to be taken out before it could be accessed for treatment. I assumed that an appointment would be made for another day, until I saw the nurse gather a scalpel and silver tray and realised it was going to happen right there and then.

The nurse started gently – a little pull here, a snip there – before realising the stitches weren’t dissolving at all. They were embedded, properly embedded, and he had to remove them manually, without anaesthetic or anything to numb the pain. At first, it was tolerable, uncomfortable but manageable, until the pain suddenly surged – sharp, hot, slicing straight into the flesh of my chest. A scalpel cuts with a precision that feels almost personal, and each deliberate movement felt like someone carving into me.

Tears streamed down my face as he kept apologising, cutting deeper to remove each stubborn black stitch while the other patients in the pod stared at their phones or the floor, unable to witness what was happening. We were all carrying our own pain; no one had space for anyone else’s. Twenty minutes passed – twenty minutes of being cut open while fully awake – before he finally stopped, apologising profusely, looking as traumatised as I was about this whole experience.

I sat there for the next five hours in misery – physically, emotionally, spiritually. I didn’t even try to hold the tears in anymore. I stared out the window, watching the sky shift from blue to late afternoon gold, trying to process what had just happened. My brain felt too scrambled, too overwhelmed. I couldn’t make sense of it. I couldn’t even explain it to myself. All I knew was that something inside me had been shaken loose.

When I got home that evening, I stripped off my shirt and caught sight of the skin around my port in the bathroom mirror. It was red. Raw. Angry. Bubbling with irritation. It looked brutalised, like something ripped out of a horror film. My chest throbbed with every breath. It made my stomach turn just to look at it.

I stood there, staring at my own reflection, unable to understand how this had become my life. How I was supposed to get up tomorrow, and the next day, and the next, and willingly walk back into that hospital to let them do it all again. There was no option to stop. No escape hatch. The only way out was through.

The resigned part of me, the part chemo had carved out, knew that I would return. That I had to. The cancer wasn’t going to cure itself. The chemicals needed to work. The port, red and wounded as it was, needed to be accessed again in just seven days. The only thing I could do was just breathe. One breath at a time. One infusion at a time. One awful, shrinking, exhausting day at a time.

Leave a comment